The overall treatment of patients with caries and periodontal disease, including associated pathologic conditions (e.g. pulpal and periapical lesions, tooth migration, tooth loss) can he divided into three different but frequently overlapping phases:

- The phase of initial, cause-related therapy is aimed at bringing caries and gingivitis under control and at arresting the further progression of periodontal tissue destruction.

- The phase of additional therapy is aimed at restoring function and esthetics.

- The phase of supportive therapy is aimed at preventing recurrence of caries and periodontal disease.

Objectives of Initial, Cause-Related Periodontal Therapy

The measures used in initial, cause-related periodontal therapy aim at the elimination of supra and subgingivally located bacterial deposits from the tooth surfaces. This is accomplished by:

- Motivating the patient to understand and combat dental disease (patient information)

- Giving the patient instruction on how to properly clean his/her teeth (self-performed plaque control methods)

- Scaling and root planning removal of additional retention factors for plaque such as overhanging margins of restorations, ill-fitting crowns, etc.

Evaluation Of The Effect Of The Initial, Cause-Related Therapy

The outcome of cause-related therapy must be properly determined. The clinical examination after this treatment must include data describing

- Resolution of gingivitis,

- Reduction of probing pocket depth and if possible changes in probing attachment levels,

- Reduced tooth mobility

- Improvement of the self-performed plaque control.

The finding made at the clinical re-evaluation will form the basis for the selection of measures to be included in the phase of additional treatment. It is usually possible at re-evaluation to classify a patient into one of the following categories:

- A patient with a proper oral hygiene standard, no gingival or minute inflammation (few sites which bleed on probing), few sites with deepened pockets and several sites which exhibit gain in probing attachment. In such a patient, no further periodontal treatment may be indicated. The patient should be enrolled in a maintenance program (Supporting Periodontal Therapy, SPT).

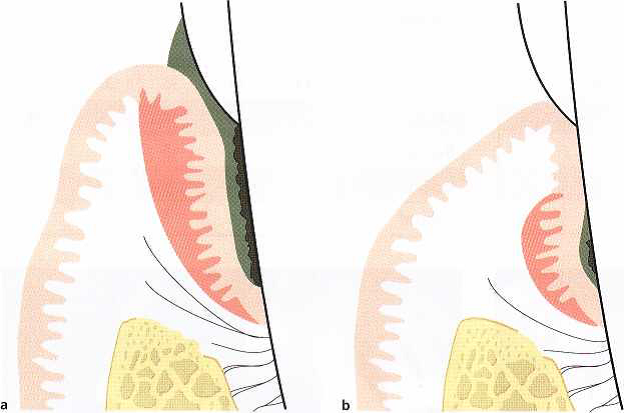

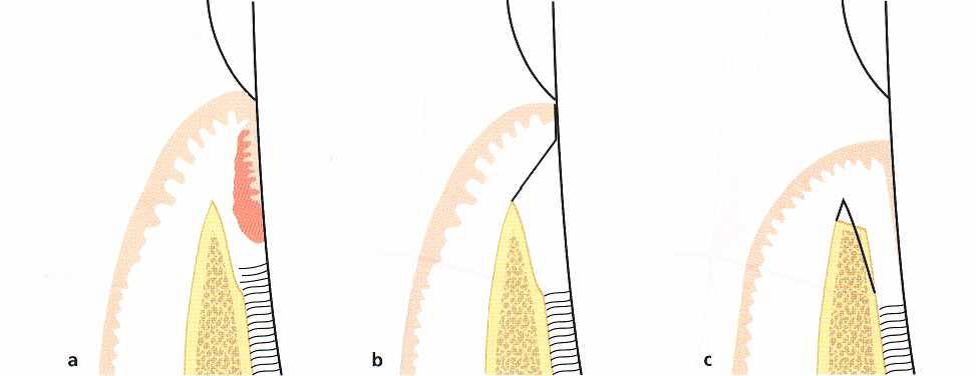

- A patient who has a proper standard of self-performed plaque control, but in whom a number of gingival sites still bleed on probing, and in whom a significant reduction of the probing depth at such sites has not been achieved. In such a patient, the additional treatment may include surgical means in order to gain access to root surfaces for a more comprehensive debridement (Fig. 1).

Fig.1. Schematic drawing illustratingA schematic drawing of a gingival unit before (a) and after (b) cause-related therapy. Clinical signs such as reduced plaque and gingivitis scores and reduced probing depth values as a result of recession indicate healing after the cause-related therapy. Remaining plaque and calculus in the apical part of the root surface of the pocket area (b) may, however, maintain the inflammatory lesion (shadowed area) in the apical part of the pocket. Probing to the bottom of the pocket will result in bleeding.

- A patient who, despite repeated instruction in self-performed plaque control, has a poor standard of oral hygiene. This patient evidently lacks motivation or ability to exercise proper home care and should not be regarded as a candidate for periodontal surgery. The patient must be made aware of the fact that even though the professional part of the initial therapy has been performed to perfection, reinfection of the periodontal pockets may sooner or later result in recurrence of destructive periodontal disease.

Since most forms of periodontal disease are plaque associated disorders, it is obvious that surgical access therapy can only be considered as adjunctive to cause-related therapy. Therefore, the various surgical methods described below should be evaluated on the basis of their potential to facilitate removal of subgingival deposits and self-performed plaque control and thereby enhance the long-term preservation of the periodontium.

The decision concerning what type of periodontal surgery should be performed and how many sites should be included is usually made after the effect of initial cause-related measures has been evaluated. The time lapse between termination of the initial cause-related phase of therapy and this evaluation may vary from 1 to 6 months. This routine has the following advantages:

- The removal of calculus and bacterial plaque will eliminate or markedly reduce the inflammatory cell infiltrate in the gingiva (edema, hyperemia, flabby tissue consistency), thereby making assessment of the “true” gingival contours and pocket depths possible.

- The reduction of gingival inflammation makes the soft tissues more fibrous and thus firmer, which facilitates surgical handling of the soft tissues. The propensity for bleeding is reduced, making inspection of the surgical field easier.

- A better basis for a proper assessment of the prognosis has been established. The effectiveness of the patient’s home care, which is of decisive importance for the long-term prognosis, can be properly valuated. Lack of effective self-performed care will often mean that the patient should be excluded from surgical treatment.

General Guidelines For Periodontal Surgery

Objectives of surgical treatment

Traditionally, pocket elimination has been a main objective of periodontal therapy. The removal of the pocket by surgical means served two purposes:

- The pocket, which established an environment conducive to progression of periodontal disease, was eliminated.

- The root surface was made accessible for scaling and, after healing, for self-performed tooth-cleaning.

In the past, increased pocket depth was the main indication for periodontal surgery. However, pocket depth is no longer as unequivocal a concept as it used to be. The probable depth, i.e. the distance from the gingival margin to the point where further periodontal probe penetration is stopped by tissue resistance, may only rarely correspond to the “true” depth of the pocket. Furthermore, regardless of the accuracy with which pockets can be measured, there is no established correlation between probable pocket depth and the presence or absence of active disease. This means that symptoms other than increased probing depth should be present to justify surgical therapy. These include clinical signs of inflammation, especially exudation and bleeding on probing (to the bottom of the pockets), as well as aberrations of gingival morphology. Finally, the fact that proper plaque control, maintained by the patient, is a decisive factor for a good prognosis (Rosling et al. 1976a, Nyman et al. 1977, Axelsson & Lindhe 1981) must be considered prior to the initiation of surgery.

In conclusion, the main objective of periodontal surgery is to contribute to the long-term preservation of the periodontium by facilitating plaque removal and plaque control, and periodontal surgery can serve this purpose by:

- Creating accessibility for proper professional scaling and root planing

- Establishing a gingival morphology which facilitates the patient’s self-performed plaque control.

In addition to this, periodontal surgery may aim at:

- Regeneration of periodontal attachment lost due to destructive disease

Indications for surgical treatment

Impaired access for scaling and root planing

Scaling and root planing are methods of therapy which are difficult to master. The difficulties in accomplishing proper debridement increase with

- Increasing depth of the periodontal pockets,

- Increasing width of the tooth surfaces,

- The presence of root fissures, root concavities, furcations, and defective margins of dental restorations in the subgingival area.

Provided a correct technique and suitable instruments are used, it is usually possible to properly debride pockets up to 5 mm deep (Waerhaug 1978, Caffesse et al. 1986). Reduced accessibility and the presence of one or several of the abovementioned impeding conditions may prevent proper debridement of shallow pockets, whereas at sites with good accessibility and favorable root morphology, proper debridement can be accomplished even in deeper pockets (Badersten et al. 1981, Lindhe et al. 1982).

It is often difficult to ascertain by clinical means whether subgingival instrumentation has been properly performed. Following scaling, the root surface should be smooth – roughness will often indicate the presence of remaining subgingival calculus. It is also important to monitor carefully the gingival reaction to subgingival debridement. If inflammation persists and if bleeding is elicited by gentle probing in the subgingival area, the presence of subgingival deposits should be suspected. If such symptoms are not resolved by repeated subgingival instrumentation, surgical treatment should be performed to expose the root surfaces for proper cleaning.

Impaired access for self-performed plaque control

The level of plaque control which can be maintained by the patient is determined not only by his/her interest and dexterity but also by the morphology of the dentogingival area.

The patient’s responsibility in a plaque control program must obviously include the cleansing of the supragingival tooth surfaces and the marginal part of the gingival sulcus. This means that the tooth area coronal to the gingival margin and at the entrance to the gingival sulcus should be the target for the patient’s home care efforts.

Pronounced gingival enlargement and gingival craters are examples of morphologic aberrations which may impede proper home care. Likewise, the presence of restorations with defective marginal fit or adverse contour and surface characteristics at the gingival margin may seriously compromise plaque removal.

By the professional treatment of periodontal disease, the dentist prepares the dentition in such a way that home care can be effectively managed. At the completion of treatment, the following objectives should have been met:

- No sub or supragingival dental deposits

- No pathologic pockets (no bleeding on probing to the bottom of the pockets)

- No plaque-retaining aberrations of gingival morphology

- No plaque-retaining parts of restorations in relation to the gingival margin

These requirements lead to the following indications for periodontal surgery:

- Accessibility for proper scaling and root planning.

- Establishment of morphology of the dento-gingival area conducive to plaque control.

- Pocket depth reduction.

- Correction of gross gingival aberrations.

- Shift of the gingival margin to a position apical to plaque-retaining restorations.

- Facilitate proper restorative therapy.

Contraindications for periodontal surgery

Patient cooperation

Since optimal postoperative plaque control is decisive for the success of periodontal treatment (Axelsson & Lindhe 1981), a patient who fails to cooperate during the cause-related phase of therapy should not be exposed to surgical treatment.

Even though short-term postoperative plaque control entails frequent professional treatments, the long term responsibility for maintaining good oral hygiene must rest with the patient. Theoretically, even the poorest oral hygiene performance by a patient may be compensated for by frequent recall visits for supportive therapy. A typical recall schedule for periodontal patients involves professional consultations for supportive periodontal therapy once every 3-6 months. Patients who cannot maintain satisfactory oral hygiene over such a period should normally be considered unsuited for periodontal surgery.

Cardiovascular disease

Arterial hypertension does not normally preclude periodontal surgery. The patient’s medical history should be checked for previous untoward reactions to local anesthesia. Local anesthetics free from or low in adrenaline may be used and an aspirating syringe should be adopted to safeguard against intravascular injection.

Angina pectoris does not normally preclude periodontal surgery. The drugs used and the number of episodes of angina may indicate the severity of the disease. Premedication with sedatives and the use of local anesthesia low in adrenaline are often recommended. Safeguards should be adopted against intravascular injection.

Myocardial infarction patients should not be subjected to periodontal surgery within 6 months following hospitalization, and thereafter only in cooperation with the physician responsible for the patient.

Anticoagulant treatment implies increased propensity for bleeding. Periodontal surgery should be scheduled first after consultation with the patient’s physician to determine whether modification of the anticoagulant therapy is indicated. In patients on moderate levels of anticoagulation and only requiring minor surgical treatment no alteration of their anticoagulant therapy may be required. To keep the prothrombin time within a safety level for hemorrhage control during surgery in patients with higher levels of anticoagulation, adjustments of the anticoagulant drug therapy usually need to be initiated 2-3 days prior to the dental appointment. Anticoagulation may be safely resumed immediately after the periodontal surgical procedure since several days are needed for full anticoagulation to return. Aspirin and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs should not be used for postoperative pain control since they increase bleeding tendency. Furthermore, tetracyclines are contraindicated in patients on anticoagulant drugs due to interference with prothrombin formation (Fay & O’Neil 1984).

Rheumatic endocarditis, congenital heart lesions and heart/vascular implants involve risk for transmission of bacteria to heart tissues and heart implants during the transient bacteremia that follows manipulation of infected periodontal pockets. Surgical treatment (including tooth extractions) of patients with these conditions, as well as of patients at risk of hematogenous prosthetic joint infection (for the first 2 years following joint placement) (American Dental Association and American Academy of Orthopedic Surgeons 1997), should be preceded by antiseptic mouthrinsing (0.2 % chlorhexidine) and prescription and administration of an appropriate antibiotic in a high dose. According to the recommendations by the American Heart Association (Dajani et al. 1997), 2 g of amoxicillin administered 1 hour before the treatment is an adequate regimen. In case the patient is allergic to penicillin, clindamycin (600 mg) is recommended as an alternative. No second doses are recommended for any of the above dosing regimens. Tetracyclines and erythromycin are not recommended for prophylactic cardiovascular antibiotic coverage.

Organ transplantation

In organ transplantation, medications are used to prevent transplant rejection. The drug of choice today is cyclosporin A, a potent immunosuppressant drug. The adverse effects seen following cyclosporin A treatment include an increased risk for gingival enlargement as well as hypertension. In addition, hypertension seen in renal transplant recipients is often treated with calcium channel blockers. These antihypertensive agents have also been associated with gingival enlargement. As in patients on phenytoin therapy, gingival enlargement in patients on cyclosporin A therapy or on antihypertensive therapy with calcium blockers may be corrected by means of periodontal surgery. However, due to the strong propensity for recurrence, the use of intensified conservative periodontal therapy to prevent gingival enlargement in susceptible patients should be encouraged.

Prophylactic antibiotics are recommended in transplant patients taking immunosuppressive drugs, and the patient’s physician should be consulted before any periodontal therapy is performed. In addition, antiseptic mouthrinsing (0.12% chlorhexidine) should precede the surgical treatment.

Blood disorders

If the medical history includes blood disorders, the exact nature of these should be ascertained. Patients suffering from acute leukemias, agranulocytosis and lymphogranulomatosis must not be subjected to periodontal surgery.

Anemias in mild and compensated forms do not preclude surgical treatment. More severe and less compensated forms may entail lowered resistance to infection and increased propensity for bleeding. In such cases, periodontal surgery should only be performed after consultation with the patient’s physician.

Hormonal disorders

Diabetes mellitus entails lowered resistance to infection, propensity for delayed wound healing and predisposition for arteriosclerosis. Well compensated patients may be subjected to periodontal surgery provided precautions are taken not to disturb dietary and insulin routines.

Adrenal function may be impeded in patients receiving large doses of corticosteroids over an extended period. These conditions involve reduced resistance to physical and mental stress, and the doses of corticosteroid may have to be altered during the period of periodontal surgery. The patient’s physician should be consulted.

Neurologic disorders

Multiple sclerosis and Parkinson’s disease may in severe cases make ambulatory periodontal surgery impossible. Paresis, impaired muscular function, tremor, and uncontrollable reflexes may necessitate treatment under general anesthesia.

Epilepsy is often treated with phenytoin which, in approximately 50% of cases, may mediate the formation of gingival enlargement. These patients may, without special restrictions, be subjected to periodontal surgery for correction of the enlargement. There is, however, a strong propensity for recurrence of the enlargement, which in many cases can be countered by intensifying the plaque control.

Smoking

Although smoking negatively affects wound healing (Siana et al. 1989), it may not be considered a contraindication for surgical periodontal treatment. The clinician should be aware, however, that less resolution of probing pocket depth and smaller improvement in clinical attachment may be observed in smokers than in non-smokers (Preben & Bergstrom 1990, Ah et al. 1994, Scabbia et al. 2001).

Local anesthesia in periodontal surgery

Traditional views of pain and discomfort as an inevitable consequence of dental procedures, in particular surgical procedures (including scaling and root planing) and extractions, are no longer accepted by patients. Pain management is an ethical obligation and will improve patient satisfaction in general (e.g. increased confidence and improved cooperation) as well as patient recovery and short-term functioning after oral/periodontal surgical procedures.

In order to prevent pain during the performance of a periodontal surgical procedure, the entire area of the dentition scheduled for surgery, the teeth as well as the periodontal tissues, requires proper local anesthesia.

General indications for various surgical techniques

Gingivectomy

The obvious indication for gingivectomy is the presence of deep supra-alveolar pockets. In addition, the gingivectomy technique can be used to reshape abnormal gingival contours such as gingival craters and gingival hyperplasias. In such cases the technique is often termed gingivoplasty.

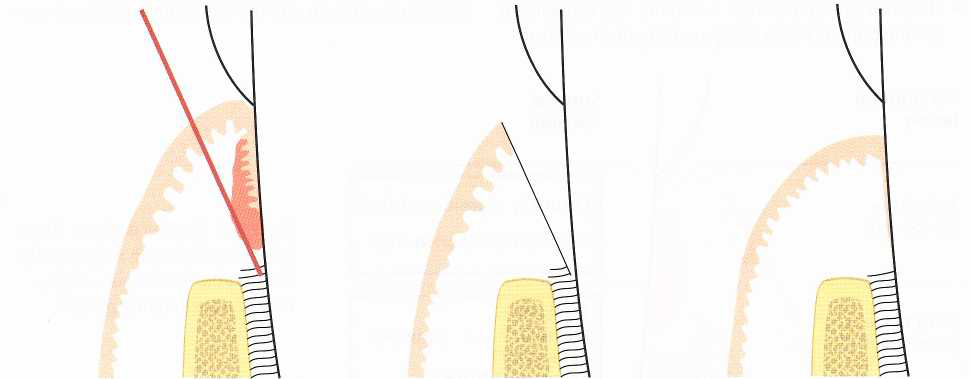

Gingivectomy is not considered suitable in situations where the incision will lead to the removal of the entire zone of gingiva. This is the case when the bottom of the probeable pocket to be excised is located at or below the mucogingival junction. As an alternative in such a situation, an internal beveled gingivectomy may be performed (Fig. 2). Furthermore, since the gingivectomy procedure is aimed at the complete elimination of the periodontal pocket, the procedure cannot be used in periodontal sites where infrabony lesions or bony craters are present.

Fig. 2 Internal beveled gingivectomy. Schematic illustration of the incision technique in case of the presence of only a minimal zone of gingiva.

These limitations, combined with the development in recent years of surgical methods which have a broader field of application, have led to less frequent use of gingivectomy in the treatment of periodontal disease.

Flap operation with or without osseous surgery

Flap operations can be used in all cases where surgical treatment of periodontal disease is indicated. Flap procedures are particularly useful at sites where pockets extend beyond the mucogingival border and/or where treatment of bony lesions and furcation involvements is required.

The advantages of flap operations include:

- Existing gingiva is preserved

- The marginal alveolar bone is exposed whereby the morphology of bony defects can be identified and the proper treatment rendered

- Furcation areas are exposed, the degree of involvement and the “tooth-bone” relationship can be identified

- The flap can be repositioned at its original level or shifted apically, thereby making it possible to adjust the gingival margin to the local conditions

- The flap procedure preserves the oral epithelium and often makes the use of surgical dressing superfluous

- The postoperative period is usually less unpleasant for the patient when compared to gingivectomy.

Postoperative pain control

In order to minimize postoperative pain and discomfort for the patient, the surgical handling of the tissues should be as atraumatic as possible. Care should be taken during surgery to avoid unnecessary tearing of the flaps, to keep the bone moistened and to ensure complete soft tissue coverage of the alveolar bone at suturing. With a carefully performed surgical procedure most patients will normally experience only minimal postoperative problems. The pain experience is usually limited to the first days following surgery and is of a level that in most patients can be adequately controlled with normally used drugs for pain control. However, it is important to recognize that the pain threshold level is subjective and may vary between individuals. It is also important to give the patient information about the postsurgical sequence and that uncomplicated healing is the common event. Further, during the early phase of healing, the patient should be instructed to avoid chewing in the area subjected to surgical treatment.

Postsurgical care

Postoperative plaque control is the most important variable in determining the long-term result of periodontal surgery. Provided proper postoperative plaque control levels are established, most surgical treatment techniques will result in conditions which favor the maintenance of a healthy periodontium.

Although there are other factors of a more general nature affecting surgical outcome (e.g. the systemic status of the patient at time of surgery and during healing), disease recurrence is an inevitable complication, regardless of surgical technique used, in patients not given proper postsurgical and maintenance care.

Since self-performed oral hygiene is often associated with pain and discomfort during the immediate postsurgical phase, regularly performed professional toothcleaning is a more effective means of mechanical plaque control following periodontal surgery. In the immediate postsurgical patient management self-performed rinsing with a suitable antiplaque agent, e.g. twice daily rinsing with 0.12% chlorhexidine solution, is recommended. Although an obvious disadvantage with the use of chlorhexidine is the staining of teeth and tongue, this is usually not a deterrent for compliance. Nevertheless, it is important to return to and maintain good mechanical oral hygiene measures as soon as possible. This is especially important since rinsing with chlorhexidine, in contrast to properly performed mechanical oral hygiene, is not likely to have any influence on subgingival recolonization of plaque.

Maintaining good postsurgical wound stability is another important factor affecting the outcome of some types of periodontal flap surgery. If wound stability is judged an important part of a specific procedure, the procedure itself as well as the postsurgical care must include measures to stabilize the healing wound (e.g. adequate suturing technique, protection from mechanical trauma to the marginal tissues during the initial healing phase). If a mucoperiosteal flap is replaced rather than apically repositioned, early apical migration of gingival epithelial cells will occur as a consequence of a break between root surface and healing connective tissue. Hence, a maintained tight adaptation of the flap to the root surface is essential and one may therefore consider keeping the sutures in place for a longer period of time than the 7-10 days usually prescribed following standard flap surgery.

Following suture removal, the surgically treated area is thoroughly irrigated with a dental spray and the teeth are carefully cleaned with a rubber cup and polishing paste. If the healing is satisfactory for starting mechanical toothcleaning, the patient is instructed in gentle brushing of the operated area using a toothbrush that has been softened in hot water. At this early phase following the surgical treatment the use of interdental brushes is abandoned due to the risk of traumatizing the interdental tissues. Visits are scheduled for supportive care at 2-week intervals to closely monitor the patient’s plaque control. During this postoperative maintenance phase, adjustments of the methods for optimal self-performed mechanical cleaning are made depending on the healing status of the tissues. Dictated by the patient’s plaque control standard, the time interval between visits for supportive care may gradually be increased.

Outcome Of Surgical Periodontal Therapy

Healing following surgical pocket therapy

Gingivectomy :

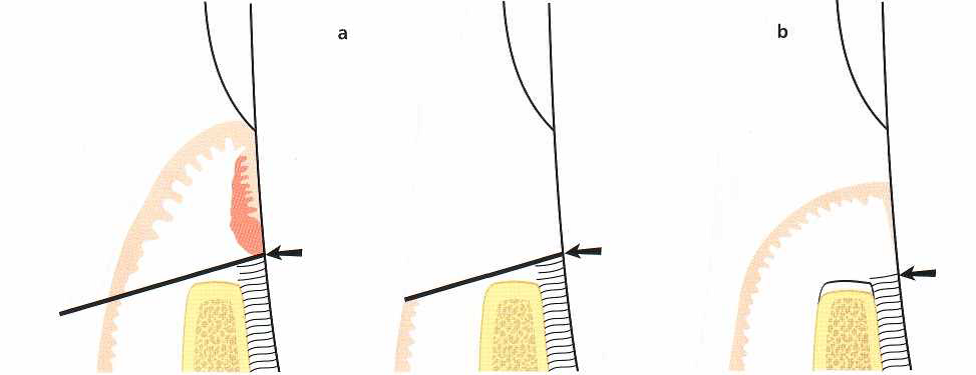

Fig. 3 Gingivectomy. Dimensional changes as a result of therapy.

- The preoperative dimensions. The line indicates the location of the primary incision, i.e. the suprabony pocket is eliminated with the gingivectomy technique.

- Dimensions following proper healing. Minor resorption of the alveolar bone crest as well as some loss of connective tissue attachment has occurred.

The apically repositioned flap :

Following osseous surgery for elimination of bony defects and the establishment of “physiologic contours” and repositioning of the soft tissue flaps to the level of the alveolar bone, healing will occur primarily by first intention, especially in areas where proper soft tissue coverage of the alveolar bone has been obtained. During the initial phase of healing, bone resorption of varying degrees almost always occurs in the crestal area of the alveolar bone (Ramfjord & Costich 1968). The extent of the reduction of the alveolar bone height resulting from this resorption is related to the thickness of the bone in each specific site (Wood et al. 1972, Karring et al. 1975).

During the phase of tissue regeneration and maturation a new dento-gingival unit will form by coronal growth of the connective tissue. This regrowth occurs in a manner similar to that which characterized healing following gingivectomy.

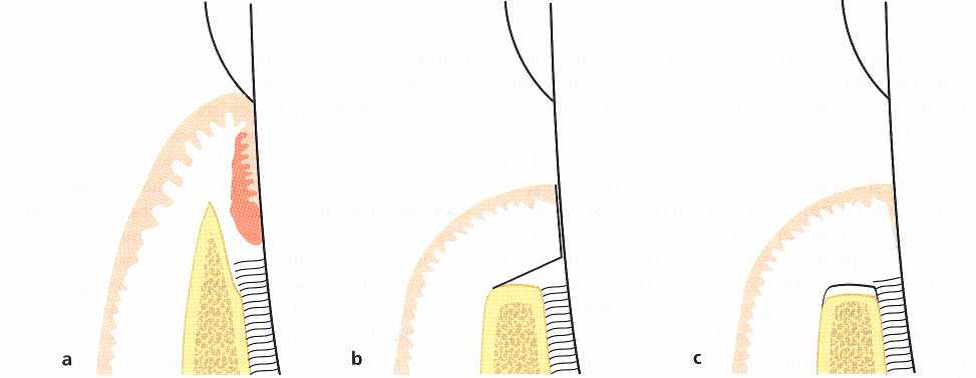

Fig. 4 Apically repositioned flap. Dimensional changes.

- The preoperative dimensions. The broken line indicates the site from which the mucoperiosteal flap is reflected.

- Bone re-contouring has been completed and the flap repositioned to cover the alveolar bone.

- Dimensions following healing. Minor resorption of the marginal alveolar bone has occurred as well as some loss of connective tissue attachment.

The modified Widman flap :

If a “modified Widman flap” is carried out in an area with a deep infrabony lesion, bone repair may occur within the boundaries of the lesion (Rosling et al. 1976a, Poison & Heijl 1978). However, crestal bone resorption is also seen. The amount of bone fill obtained is dependent upon

- The anatomy of the osseous defect (e.g. a three-walled infrabony defect often provides a better mould for bone repair than two-walled or one-walled defects),

- The amount of crestal bone resorption, and

- Extent of chronic inflammation, which may occupy the area of healing.

Interposed between the regenerated bone tissue and the root surface, a long junctional epithelium is always found (Caton & Zander 1976, Caton et al. 1980). The apical cells of the newly formed junctional epithelium are found at a level on the root that closely coincides with the presurgical attachment level.

Soft tissue recession will take place during the healing phase following a modified Widman flap procedure. Although the major apical shift in the position of the soft tissue margin will occur during the first 6 months following the surgical treatment (Lindhe et al. 1987), the soft tissue recession may often continue for more than 1 year. Among factors influencing the degree of soft tissue recession, besides the period for soft tissue remodeling, are the initial height and thickness of the supracrestal flap tissue and the amount of crestal bone resorption.

Fig. 5 Modified Widman flap. Dimensional changes.

- The preoperative dimensions. The broken line indicates the site from which the mucoperiosteal flap is reflected.

- Surgery (including curettage of the angular bone defect) is completed with the mucoperiosteal flap repositioned as close as possible to its presurgical position.

- Dimensions following healing. Osseous repair as well as some crestal bone resorption can be expected during healing with the establishment of a “long” junctional epithelium interposed between the regenerated bone tissue and the root surface. An apical displacement of the soft tissue margin has occurred.

References:

- Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry 4th edition Jan Lindhe Thorkild Karring, Niklaus P. Lang

- Carranza’s Clinical Periodontology 9th Edition Michael G. Newman, Henry H. Takei, Fermin A. Carranza.

- Atlas Of Cosmetic And Reconstructive Periodontal Surgery, Third Edition, Edward S. Cohen, Dmd

- Practical Advanced Periodontal Surgery, Serge Dibart

Figure References:

- Clinical Periodontology and Implant Dentistry 4th edition Jan Lindhe, Thorkild Karring, Niklaus P. Lang

| Last Reviewed | : | 9 January 2017 |

| Writer | : | Dr. Amirham bt. Ahmad |

| Accreditor | : | Datin Dr. Indra a/p Nachiapan |