Introduction

Gum disease, or periodontal disease as it is more correctly known, starts as “gingivitis”, an inflammation of the gums around the teeth, often characterised by tenderness, redness and bleeding during brushing. If untreated, it may develop into chronic degenerative disease of the gums, characterised by further gum inflammation, bad breath, discharge of pus and loosening of the teeth. As inflammation progresses, the gums recede from the teeth allowing deeper tissues -the collagen, ligaments and bone supporting the teeth – to become affected, also known as “periodontitis”. As it becomes more advanced, deep pockets form between the teeth and the surrounding gingiva, bone loss continues and teeth may fall out. Periodontal disease is highly prevalent in the community with data suggesting that periodontal diseases affects approximately 95% of Malaysia population of the age of 35 to 44 years olds(1).

Figure 1: Gingivitis |

Figure 2: Periodontitis |

What causes periodontal disease?

Bacteria in the mouth are implicated in almost all forms of gum disease, through the development of plaque. Plaque gradually becomes mineralised and hardens into tartar or calculus, through the action of sialic acid in the saliva. It cannot then be removed by brushing and provides an anchorage for further build-up of bacteria. Plaque-forming bacteria produce free radicals, toxins, and connective tissue-destroying enzymes which initiate the inflammatory process.

Gingivitis and periodontitis are characterized by a dysregulated host inflammatory/ immune response to plaque bacteria in susceptible individual, however the host response exhibits wide heterogenecity in common with other chronic inflammatory diseases, and with relatively minor shifts in host response resulting in disease progression in susceptible person.

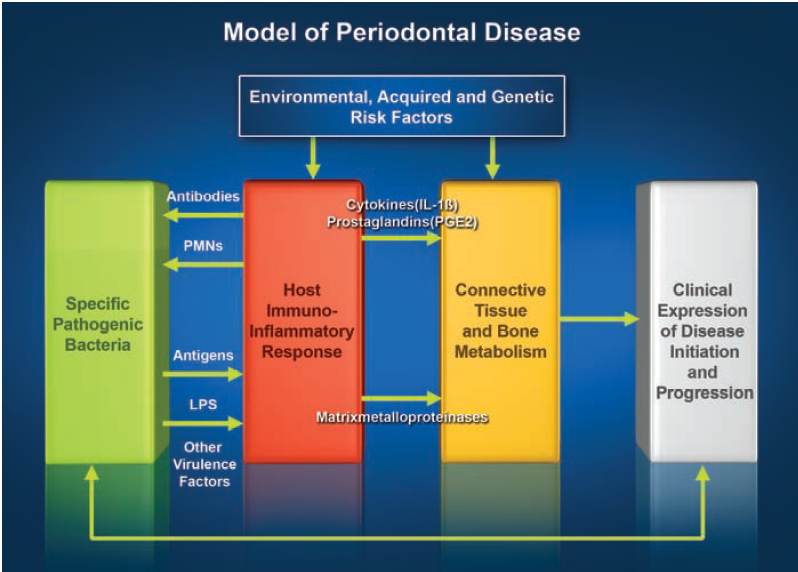

A variety of risk factors have been identified that modified the host response and thereby tip the biological balance from health to disease. These factors can be characterised as genetic, environmental (e.g. stress, bacterial challenge) and lifestyle/ behavioural (e.g. exercise, nutrition, smoking). Risk factors are important in the development and propagation of periodontal disease and act predominantly via modification of the host response to bacterial challenge, resulting in less effective clearing of pathogenic species and inflammation resolution which in turn increases host mediated tissue damage (2,3).

Figure 3: Model of periodontal disease

Role of nutrition in periodontal disease

Nutrients can be divided into 6 major classes i.e. fats, carbohydrates, proteins, minerals, vitamins and water. These can be further subdivided into 2 broad categories, “macronutrients” (fats, carbohydrates and proteins) which are required in large quantities from the diet and “micronutrients” (minerals, vitamins, trace elements and amino-acids) which are only required in small quantities in the diet and which are essential for a range of biological processes important in supporting optimal health.

It has been acknowledged for many years that nutritional intake can impact upon the levels of inflammation seen in a number of diseases, and this is no less the case in periodontitis. Research studies using an experimental gingivitis model have shown increased levels of bleeding and probing when participants were fed with a diet high in carbohydrates when compared to those on low sugar diet (4). Perhaps the biggest factor in the build-up of plaque is sugar (and to a lesser extent other refined carbohydrates) in the diet. These foods create acidic conditions in the mouth that are ideal for the proliferation of plaque-forming bacteria. Just as importantly, sugar consumption depresses the immune system, particularly by inhibiting the action of neutrophils (5).

This finding has been further supported by a study investigating volunteers placed on a primitive diet which was high in fibre, anti-oxidants and fish oils, but low in refined sugars and with no oral hygiene measures. As would be expected plaque levels increased significantly and classic periodontal pathogens emerged within the biofilm, but unexpectedly gingival bleeding significantly reduced from 35% to 13% (6). These studies support a role for nutrition in controlling periodontal inflammation. However to date the precise mechanisms underpinning this observed dietary effect have yet to be fully elucidated.

Several nutritional deficiencies are associated with periodontal disease. The best documented is vitamin C, whose deficiency ultimately causes scurvy, a disease characterised by bleeding, suppurating gums and the loss of teeth. Vitamin C is vital in forming the amino acids needed for the production of collagen, an important component of the tissues that support the teeth. Vitamin C is needed too, for bone formation and calcification, and for wound healing (7). Low levels of vitamin C have been shown to be associated with an increased risk of periodontal disease (8), increased permeability of the oral mucosa to bacterial toxins (9), as well as with impaired immune response. Deficiencies of vitamins A and E may also predispose to periodontal disease (10).

Deficiencies of protein, vitamin D or calcium may lead to the resorption of bone around the teeth and destruction of the periodontal ligaments that anchor the teeth to the jawbones. Women with severe osteoporosis are three times more likely to experience tooth loss (11). Reduced gastric acidity is associated with resorption of calcium from the bone supporting the teeth. This is probably because calcium absorption from the gut is decreased when gastric hydrochloric acid levels are low, leading to calcium deficiency. Vitamin D is essential for calcium absorption from the gut and helps maintain the proper balance of calcium and phosphorus in the bones.

Conventional treatment for periodontal disease

The care of a periodontal specialist, combined with good oral hygiene and plaque control measures, is essential in treating gum disease. A periodontist will use techniques such as scaling to remove plaque deposits above and below the gumline, root planing to smooth rough root surfaces so that the gum can heal, and oral irrigation to flush out bacteria and toxins. If very deep pockets have formed around teeth and bone has been lost, periodontal surgery may be recommended to remove gum flaps, so that the roots of the teeth are accessible for cleaning.

Nutritional therapy for periodontal disease

In general terms, the diet that provides for good gum health is no different from that which provides for optimal health of the whole body. It should be nutrient-rich and based on fresh natural foods, whole grains, vegetables, fruit, fish, beans and seeds. It should be low in sugar, refined carbohydrates, salt and alcohol and should avoid damaged fats, artificial additives and allergenic foods. Foods that are high in bioflavonoids, such as blue-black fruits, onions, citrus pith and hawthorn berries should be included as these compounds are important in maintaining healthy collagen structure (12). A diet that is high in fibre may protect against gum disease by promoting the secretion of saliva (13). Specific nutritional supplements have been used with success in the treatment of periodontal disease. The following daily supplement programme is likely to be helpful.

Coenzyme Q10 (50 to 150 mg).

Coenzyme Q10 (Co Q10) is chemically similar to vitamin E and is involved in electron transfer in the mitochondria. Early work suggested that people with periodontal disease may be deficient in Co Q10.(14) In double blind trials, 50mg a day of Co Q10, given for three weeks, led to a significant reduction in the symptoms of gingivitis.(15) More recent studies have shown that the topical application of Co Q10 may also improve periodontitis (16), although the conclusions of this research have been questioned.(17)

Vitamin C (2 to 4g).

Vitamin C supplementation can improve the symptoms of periodontitis in people who have a low intake of the vitamin (below 35 mg daily) (18), although there is less evidence that it benefits people who already consume adequate amounts in their diet. (19) However, vitamin C is necessary to maintain a healthy immune system, to combat free radical damage and to promote healing. A daily supplement would seem sensible.

Bioflavonoids (500mg to 1g).

The bioflavonoids that often accompany vitamin C in foods, which are important for collagen structure, can reduce gum inflammation when taken as a supplement. (20)

Beta-carotene (100,000i.u).

Vitamin A is necessary for collagen synthesis and wound healing, maintaining the integrity of periodontal tissues and enhancing immune function. Beta-carotene may be the best form of vitamin A to take, due to its affinity with gum tissue, potent antioxidant activity and safety at high dosages. (21)

Zinc (15-30mg).

Zinc functions synergistically with vitamin A, inhibits plaque growth and helps to stabilise membranes in the periodontal tissues. (22) Citrate or picolinate are the best forms to take.

Vitamin E (200 to 400 i.u).

Vitamin E has been shown to be of benefit in severe periodontal disease, due to its antioxidant and wound healing properties.

Selenium (200mcg).

Selenium and vitamin E act synergistically as antioxidants.

Folic acid (2mg).

Double blind studies have shown that folic acid can significantly reduce gum inflammation. (23) This is a particularly important supplement for women who are on the contraceptive pill or are pregnant.

References

- National Oral Health Plan For Malaysia 2011-2020. Oral Health Division, Ministry of Health Malaysia. February 2011.

- Page R.C., Kornman K.S. The pathogenesis of human periodontitis: an introduction. Periodontology 2000. 1997; 14: 9-11

- Van Dyke T.E. Prosolving lipid mediators: potential for prevention and treatment of periodontitis. Journal of Clinical Periodontology 2011; 38 (suppl 11): 119-125.

- Sidi A., Ashley F. Influence of frequent sugar intakes on experimental gingivitis. Journal of Periodontology 1984; 55: 419-423.

- Ringsdorf W., Cheraskin E. and Ramsay R. Sucrose, neutrophil phagocytosis and resistance to disease. Dental Survey 1976 ; 52: 46-58.

- Baumgartner S., Imfeld T. and Schicht O. The impact of Stone Age diet on gingival conditions in the absence of oral hygiene. Journal of Periodontology 2009 ; 80: 759-768.

- Woolfe S., Hume W. and Kenney E. Ascorbic acid and periodontal disease: a review of the literature. Journal of Western Society Periodontol 1980;28:44-60.

- Vaananen M., Markkanen H. and Tuovinen V. Periodontal health related to plasma ascorbic acid. Proc. Finn. Dent. Soc 1993;89:51-59.

- Alvares O. and Siegel I. Permeability of gingival sulcular epithelium in the development of scorbutic gingivitis. J. Oral Path 1981;10:40-48. Carranza F. Glickman’s Clinical Periodontology. W. B. Saunders 1984.

- Carranza, F. Glickman’s Clinical Periodontology. W. B. Saunders 1984.

- Jeffcoat et al. Systemic osteoporosis and oral bone loss: evidence shows increased risk factors. J. Am. Dental Assoc, Nov 1993, 49-56.

- Rao C., Rao V. and Steinman B. Influence of bioflavonoids on the metabolism and cross linking of collagen. Ital. J. Biochem 1981;30:259-70.

- Alvares, O. Nutrition, diet and oral health. Chapter 14 in Worthington-Roberts, B. (Ed.), Contemporary developments in nutrition. Mosby 1981.

- Nakamura R., Littarru G. and Folkers K. Deficiency of coenzyme Q in gingiva of patients with periodontal disease. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res 1973;43:84-92.

- Wilkinson E. et al. Adjunctive treatment of periodontal disease with coenzyme Q10. Res. Commun. Chem. Pathol. Pharmacol 1976;14:715-9.

- Hanioka T., Tanaka M., Shiskuisi S. and Folkers K. Effect of topical application of coenzyme Q10 on adult periodontitis. Mol. Aspects Med 1994;15:Suppl:241-8.

- Watts T. Coenzyme Q10 and periodontal treatment: is there any beneficial effect? Br. Dent. Journal 1995;178: 209-13.

- Aurer-Koselj J., Kralj-Klobucar N., Buzina R. and Bacic M. The effect of ascorbic acid supplementation on periodontal tissue ultrastructure in subjects with progressive periodontitis. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res 1982;52:333-41.

- Vogel R., Lamster I., Wechsler S. et al. The effects of megadoses of ascorbic acid on PMN chemotaxis and experimental gingivitis. J. Periodontol 1986;57:472-9.

- Carvel I. and Halperin V. Therapeutic effect of water soluble bioflavonoids in gingival inflammatory conditions. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol 1961;14:847-55.

- Burton G. and Ingold K. Beta-carotene: an unusual type of liquid antioxidant. Science 1984;224:569-73.

- Hsieh S., Hayali A. and Navia J. Zinc. Chapter 9 in Curzon, M. and Cutress, T. (Eds), Trace Elements in Dental Disease. John Wright, Boston 1983.

- Pack A. and Thomson,M. Effects of extended systemic and topical folate supplementation on gingivitis of pregnancy. J Clin. Periodontol 1982;9:275-80.

| Last Reviewed | : | 13 June 2016 |

| Writer | : | Dr. Aisah bt. Ahmad |

| Accreditor | : | Dr. Chan Yoong Kian |